Article:

Velocity, For You or Against You?

By Richard J. Maybury

Reprint from the June-July 2008 EWR

The promise of this newsletter is that you will know what others don’t. This is important not just for attracting a crowd of admirers at a social gathering, but for being ahead of the game in the investment markets, too.

It also helps you develop personalized tactics for your business or career, to make you a winner instead of a loser from the turmoil.

This is especially true for velocity. If you are not careful to make sure it helps you, it will hurt you.

Over the next few years, I suggest you keep this EWR close at hand as a ready reference, because velocity will probably dance around a lot, and every few months you may want to review this article to keep a tight grip on what’s happening.

No one I know of writes much about velocity, so you aren’t likely to find this information anywhere else. That is why I’m covering it in detail.

However, velocity and money demand are very nebulous subjects, we have few reliable data to shed light on them. I’m writing mostly from my decades of experience and logic, not from controlled studies. This isn’t science, it’s guesswork. I’m being intuitive, because that’s all an explanation of velocity and money demand can be; take everything I’m saying with a grain of salt.

So, let’s get started. As I said in the April EWR, I think…

…the Fed’s bungling in August…

…broke velocity loose from its moorings.

During times when velocity is stable, you don’t need to know much about it. But when it becomes erratic, as I think it has now, a deep understanding is crucial.

This leads to two questions: how do we know what the level of velocity is, and how do we know it’s changing?

The answer to both questions is…

…we don’t. I will explain shortly. First, here is a quick refresher on velocity and money demand.

Velocity is the speed at which money changes hands. It is a measure of demand for money.

When people are reluctant to spend their dollars, demand for the dollar is up, and the speed with which dollars change hands is reduced. Money demand up, velocity down.

When people are more willing to spend, money demand is down, and the money changes hands more quickly. Money demand down, velocity up.

When we spend, the money is in circulation, helping to drive prices up.

If we don’t spend, it’s as if the money is taken out of circulation and hidden. Money that’s circulating more slowly is creating less demand for goods and services, and less pressure to drive prices up.

Clearly, a dollar that participates in no transactions has no effect on prices. One that participates in twice as many transactions as some other dollar has twice the effect on prices.

As explained in my little Uncle Eric book The Money Mystery…

…inflations typically go through three stages…

…caused by changes in money demand and velocity. For good planning and decision making, it is now crucially important to understand these stages. Here is an excerpt from that book:

Dear Chris,

In my previous set of letters, I mentioned the three stages of inflation. In the first stage, prices do not rise as fast as the money supply, because people don’t know what is happening. Some delay their spending in hopes prices will fall back. In effect, they take some money out of circulation as the government is pumping it in. That was France in 1790.

In the second stage, many people have caught on, and are spending their money quickly. Prices rise faster than the money supply because each unit of the money is changing hands faster. Many people want to get rid of it quickly and are willing to accept less for it.

In the third stage, the runaway, the whole population is in a panic to get rid of the money as soon as they get their hands on it, and the money declines to its real value, which is the value of scrap paper.

In other words, in stage one, the currency is not losing its value very fast because people still trust it.

In stage two, the currency is in trouble. In the last half of stage two, it’s circling the drain.

In stage three, it’s going down the drain.

Let me emphasize…

…velocity is mysterious

It is to economics what subatomic particles are to physics. The math shows it’s there, and we can observe its effects, but no one has ever really seen the thing itself. (Pull a quarter from your pocket, then look behind you. Is anyone following this coin to see how many times per year it’s transferred from one person to another?)

Again, velocity is the speed at which money changes hands. It’s the measure of the demand for money.

We know velocity exists, because we know demand for money exists. I want money, you want it, and so does everyone else. But although money supply is a big public issue, money demand and velocity are not. Why, I don’t know.

The reason may be that velocity data are among the most worthless of all of economic statistics.

The most widely cited velocity measure, which divides Gross Domestic Product by money supply, assumes it is possible to know what GDP is.

Ask any accountant how accurately the performance of a large corporation can be measured. So, how can we know GDP, which is the total performance of all businesses, plus all households and government agencies?

Treasury Secretary William Simon once said he was convinced that economists use decimal points to show they have a sense of humor.

I rarely pay much attention to…

…official statistics about velocity, and instead look at the kind of numbers that are verifiable facts: prices. A price is not a statistic, it’s an event. Two humans have made a trade, and the exchange rate in that trade is the price.

If they traded an apple for an orange, the price of the orange was an apple, and the price of the apple was an orange.

If they traded a dollar for an orange, the price of the orange was a dollar, and the price of the dollar was an orange.

If more people arrive at the site of the trade to offer more dollars for the orange, then the price of the orange goes up because the money supply surrounding the orange has increased. Probably, these people have more dollars, or their demand for dollars has fallen, or both.

A key phrase here is, “these people.” Others may feel differently about their dollars, or they may have a larger or smaller supply of them.

The average velocity in a given household, geographic area, or market — say, the dotcoms in the 1990s, or subprime real estate in 2006 — can be different than the average for the whole economy.

But if two conditions exist, we can be reasonably certain money demand, on average, is falling and velocity is rising: (1) prices are rising faster than money supply and (2) many people are expressing a fear of holding dollars.

Money demand and velocity are not uniform

All over the country and the world, they vary from one person to the next, and they change constantly.

Again, the main thing I watch for is the two conditions: widespread changes in prices that are greater than changes in money supply, accompanied by public comments about falling demand for the money.

For instance, the federal government admits it has been inflating the money supply heavily. John Williams at www.shadowstats.com reports that the M3 measure of money supply he derives from the government’s statistics is now rising at an annual rate of 16.4%. Yet, bad as 16.4% is, numerous prices have been rising much faster, including those of wheat, gasoline and euros.

This while, at the OPEC1 conference on November 18, 2007, the Saudi foreign minister “accidentally” left his microphone open when he spoke a warning about a “dollar collapse,” meaning a flight from the dollar.2

Kenneth S. Rogoff, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund recently told the New York Times, “These central banks know that holding these low-yielding Treasury bills is just an aid program to the United States, and they want to get out of the business.” He said “They are keen to diversify” out of dollars.3

Said the Times in that article, “the dollar has been slipping as a percentage of foreign currency reserves, as nations increasingly sock away other currencies. … Between 2001 and the end of 2007, the dollar’s share of total foreign exchange reserves shrank from about 73 percent to 64 percent.” Also, “People in international financial circles detect a subtle shifting in the ground in confidence about the dollar.”4

The government of Libya has restricted sales of oil for dollars, preferring instead euros or yen.5

Except for the Arab oil dictators in the Persian Gulf, few governments still peg their currencies to the dollar. Since 2005, the government of China has allowed its currency to rise 18% against the dollar. Brazil’s currency has risen more than 100% against the dollar since 2003.6

So, we already know that since the beginning of the war, the dollar price of raw materials and a great many other things has risen dramatically — much more so even than the reported increase in the supply of dollars — and now we have people who are close to the commodity and currency markets reporting that governments and the super wealthy are trying to get out of dollars.

Demand for dollars down, velocity up.

How do we know…

…the extent to which velocity has been rising? We don’t. Again, velocity statistics are notoriously awful.

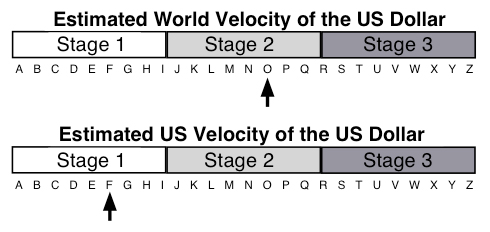

In this chart, I’ve used a scale of letters instead of numbers, because I don’t want anyone assuming I’ve found a way to measure the number of times the average dollar changes hands. The chart is my guess at where we are in the three stages of inflation.

It’s intuitive, not scientific, based on almost four decades of studying and observing changes in money supply, prices and related factors. It could be entirely wrong, but I don’t know what to give you that would be better.

From now on, I will print the chart in each EWR until I think velocity has stabilized to the point where you no longer need pay much attention to it.

I expect this to be many years. Evidence indicates that in America’s 1970s inflation, global velocity of the dollar was unhinged by Nixon’s economic bungling in 1971, and it stayed erratic until the early 1990s.

On the chart, I’ve set the world arrow at O — beginning to circle the drain. The US arrow is at F, because my impression is that most Americans are just now catching on to what has long been widely understood outside the US. (Americans are always the last to know what their government is doing to them.) Also, fear of a recession tends to make people hungry for cash, which pushes velocity down, and this is probably a big factor inside the US. Outside, fear of recession is less, and fear of the dollar far greater.

What seems likely to me is that the stage two pressure outside the country will force its way inside, via foreigners refusing to accept dollars.

This brings us to strategies for making this disaster generate profits instead of losses for you.

Be wealthy, but don’t have money

For coping with the rising velocity of the dollar, the single most important thing is to be aware that having a lot of money isn’t the same thing as being wealthy.

During the great French inflation of the 1790s, much of the population acquired huge wads of cash. Early on, they felt quite rich, but by 1795, a hat, for instance, that had cost 14 francs in 1790, had risen to 500 francs.7

In 1913, in Germany, a typical pair of shoes cost 12 marks. By mid-1923, Germany was in stage three of the inflation, and people had so much money, they needed to carry it in wheelbarrows. The cost of the shoes had soared to a million marks. In another six months it was 32,000 times higher than that. People were swimming in marks, but many starved to death because they couldn’t afford food. A kilogram of beef cost 5,600 million marks.8

In America in 1779, George Washington complained that “a wagon-load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon-load of provisions.”9

In the South during the 1860s, everyone had lots of money, but prices rose for years at an average rate of 10% per month. The typical item that cost one dollar in 1861 was 92 dollars in 1865.10

In all these examples, people had so much money they could not count it, but they were dirt poor, because they did not have wealth.

Wealth is goods and services — homes, food, land, cars, TV sets, clothing, oil, gasoline, gold, silver, copper, food, haircuts, boats, paint jobs, art, and on and on. Real stuff. Money is just the tool we use to measure and trade wealth.

Money is also a store of value. Except when it’s not. And when it’s not — during stage two and stage three of an inflation — then you don’t want it. You want wealth, especially the kinds of wealth that retain their value.

A dish of ice cream is a very poor store of value, as are yesterday’s newspaper, a tattoo and a ten-year old computer program.

Much better are fine art, gold coins, land and classic cars. In a stage two or three inflation, to have a lot of these is to be genuinely wealthy, while having piles of money is a ticket to the poor house.

Investments…

…are a fast moving world market, so investing must be based on a world view, always.

If I am right that the world is solidly into stage two, then your “long” speculations, which are bets that a value will go up, should be in non-dollar assets. “Short” ones, which are bets that the value will go down, should be in dollar assets.

This is a generalization; there are exceptions, especially in day-to-day trading. But for anything more than, say, three months out, you are, in my opinion, taking a major risk if you are long on the US dollar.

That goes for bonds, CDs and anything else that has its value tied rigidly to that of the greenback. The evidence mentioned earlier is highly persuasive: many big dollar holders in other countries are edging toward the exits, and one of them could trigger a stampede at any time. Outside the US, the dollar could quickly go from stage two to stage three.

That’s why, in my opinion, it’s important to always have a lot of non-dollar assets.

Note this: the Fed’s excess dollars will chase anything that is “hot,” meaning anything for which demand is far greater than supply. In the 1920s and 1990s it was stocks. In the early part of the war, it was housing. Now it’s oil and food.

Right now, on my velocity chart…

…widespread fear of a recession in the US has led me to set the US arrow at F. A few months ago, I would have put it at H. Ergo, I’m thinking we’ve had a fall in velocity, which is deflationary or, some would say, disinflationary.

“Rising [oil and gasoline] prices are less a reflection of inadequate supply than they are of the dollar’s collapse. For proof, look no further than Europe, where gas prices haven’t risen nearly as sharply as they have in the U.S.” - Wall Street Journal 18th May 2008 p. A10

Consequently, several of our investments are down from where they were last year, so I see this as a buying opportunity for anything that typically does well in wartime (which is practically the only kind of investment I recommend these days).

I warned about this economic chaos on page 7 of the 9/05 EWR, and pages 6 and 7 of the 11/06 EWR, and elsewhere. Perhaps the best summary was “Ride the Coming Rollercoaster” and “When to Sell” in the 2/05 EWR. Now the economic chaos is here, and those articles are more important than ever. We’ve posted the two 2/05 articles on the Subscriber Access part of our web site. Please read them ASAP.

When I make these kinds of warnings, you might want to underline them, then on your calendar, place reminders to review the warnings every few months.

I have no plans to sell any of my wartime investments until the war ends, which could be decades.

The German example

Consider two theoretical companies. One owns a mountain of cash, and the other owns mostly land, machinery, patents, a good workforce and inventory. During stage two or stage three, which one do you buy stock in, the one with money or the one with wealth?

In stages two and three, the money is fast losing value, so you want the company with real wealth.

This isn’t to say a firm with lots of real wealth is a sure thing. Whether a stock or anything else is eventually bid up to where it ought to be depends mostly on fashion. If it catches the eye of the crowd, fine, but if it doesn’t, you can be left with an asset that ought to be highly valuable but isn’t.

This happened in the 1970s. US stocks were amazingly cheap, wonderful bargains, but people were afraid to buy them, and they went nowhere.

In the 1920s, stocks of German firms that had lots of real wealth emerged from the great German hyperinflation with only a sixth of the value they had at the start.11 This was better, of course, than losing everything, but it didn’t compare with investments in, for instance, certain foreign currencies and gold, which retained all their value. These were widely traded globally, and so were not as vulnerable to the whims of fashion in a single country.

That’s an important lesson. To reduce risk, buy non-dollar assets that are traded not only nationally but world wide.

For instance, which do you think is likely to become more fashionable, stock in Lockheed, or real estate in Bustedflush, Wyoming?

Another good generalization is that no investment stays uniformly hot throughout all three stages of an inflation. Fashion changes. A particular investment will go out of style, then in, then out, etc. You might use a strategy of buying when it’s out, and selling when it’s in. My little Uncle Eric book The Clipper Ship Strategy will help you recognize these cases.

In your business, career and daily living

Suppose we are hit by a global stampede out of the dollar. You can expect prices of consumer goods and practically everything else in the US to rise quickly, as fear of the dollar begins to spread from foreigners to Americans.

In that case, go on an emergency shopping spree, using your dollars to buy, buy, buy, while the people around you are still trying to figure out what it all means.

In other words, in the US, those who understand velocity have a tremendous advantage, because most Americans are still in the dark, and they won’t be as quick to react to a currency crisis. When the crisis hits, you may be able to get rid of your dollars before prices have adjusted very much.

A precaution you can take right now

In stage one, business people talk a lot about “pricing power.” Sellers do not have the ability to raise their prices to cover their rising costs, because their customers become angry.

In stage two, people have become resigned to rising prices and no longer show much resistance to them. Talk of pricing power difficulties goes away.

In stage three, no one pays much attention to price at all, they just want to escape from the money before it becomes worthless.

So, in any long-term contract — say six months or more —try to make sure the other party owes you non-dollars, and you owe them dollars.

In cases where you cannot avoid being owed dollars, try to get some kind of inflation indexing, so that you receive more dollars as the value of the dollar falls. If you are a manufacturer, you might, for instance, try to tie the price you receive to the Producer Price Index, which you can find at www.stlouisfed.org. It’s a far-from-perfect solution, but better than nothing.

If you can arrange it, being paid in a basket of the better foreign currencies is also preferable — perhaps a mixture of euros (the “anti-dollar”), Swiss francs, yen, New Zealand dollars and gold.

In some business deals, you can use the futures markets. For example, if you are signing a “time-and-materials” contract for the construction of a building, specify that the contractor lock in the prices of the lumber by using commodity futures. If he doesn’t know how to do it, his lumber supplier might, or he can contact a commodity broker.

These ideas may sound strange to you now, and they certainly will to the Americans you deal with. But I think it is highly likely that a year after the US is solidly into stage two, these kinds of arrangements will be common.

Two years into stage two, these arrangements will be expected, and if you don’t propose them, the other party will look at you as if you are crazy.

Own non-dollars, and owe dollars. Start thinking along these lines now. The early bird gets the worm.

Think outside the box

As teenagers in school, we were taught that the Federal Reserve is our protector. The actual fact is that for investors the Fed is a menace to navigation.

Stage two, when most prices are rising faster than money supply, is when people who are incapable of thinking outside the political box they were taught as teens begin to suffer greatly. They believe wealth is the same thing as money, so as the savvy people trade away money to get wealth, these unfortunates happily trade away their wealth for money.

It’s in stage two that the general public begins getting interested in gold, silver and the other alternatives to the dollar, driving them to spectacular new heights. In stage one, only the highly knowledgeable early birds are interested; the general public still trusts the currency.

Inside the US, where we are still in stage one, owning dollars is a near certain way to suffer a loss, but not a big one, yet. In much of the rest of the world, which I think has been in stage two for more than a year, owning US dollars has been a financial calamity. A German, for instance, who traded euros for greenbacks just before the war began has lost almost half his investment.

Incidentally, when I speak of rising prices, I’m not referring just to the “inflation” the government and mainstream press focus on. I’m talking about any and all prices, including those of stocks, real estate, raw materials, intermediate materials, farmland, patents, art, antiques or anything else that can be purchased with money. In short all prices, not just items bought by consumers.

Federal counterfeiting

Again, I believe any discussion about velocity and money demand must be based on intuition, not science, because I’ve never seen any velocity data I consider reliable. Take all my remarks with a large grain of salt.

That said, again, a few months ago I would have estimated US velocity at H. Now, my guess is that the Fed is inflating so strongly, to halt the recession, that by the elections we will be back at H or I.

If they don’t pull a replay of Volcker’s drastic emergency tightening in 1979 (see the 9/05 EWR pages 4 to 7) which I give a 25% probability, then by this time next year I expect we will be in stage two, and non-dollar assets of almost every type will be in full gallop.

To me, present conditions look like a buying opportunity, and I recently picked up more Vista Gold (VGZ, Amex). I also like Silver Standard (SSRI, Nas). For either, I think the risk level (on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being safest) is 3.0, and five year profit potential, 1,000% in terms of today’s dollar. [VGZ and SSRI have since been sold.]

If you do not have a broker who is experienced in raw materials, I recommend Global Resource Investments, 800-477-7853. They are very familiar with both VGZ and SSRI.

However, that 25% probability is why I think most of your money should remain in the Permanent Portfolio part of Harry Browne’s plan.12 Don’t put anything into your Variable Portfolio that you cannot afford to lose.

I remember in the mid-1970s, hearing newsman Walter Cronkite say the reason we are in an inflationary mess is that the Federal Reserve is counterfeiting dollars. Yes, he actually used the word counterfeiting. In a nationwide broadcast.

So much has been forgotten since those days that in the mainstream press I no longer see any article that challenges the Fed’s authority to tinker with the money supply. The Fed and its scheming are taken as a given, a fundamental part of the universe, and all anyone talks about is, how much and when the Fed should inflate the money supply.

Never mentioned is the fact that no human or group of humans has enough wisdom or honesty to be trusted with the legalized privilege of counterfeiting money.

I believe the federal counterfeiters absolutely do not want the public to understand velocity, so the mainstream press never says a word about the three stages, and virtually all their readers are in the dark about them.

This is dangerous. You need to keep track of what stage we are in, to know how to handle your business, career and investments.

Again, I suggest you keep this EWR close at hand as a ready reference, because over the next few years, velocity will probably jump around a lot, and every few months you may find it helpful to review this article to keep a command of what’s happening.

I will run the velocity chart in each EWR, and comment when necessary.

Summary & Conclusion

Velocity and money demand are a forgotten subject, difficult to understand and impossible to measure.

The most important tactic for sailing through this storm is to bear in mind the difference between money and wealth.

It’s not money that makes life better, it’s wealth. You don’t want to have a lot of money, you want wealth.

In stage one of an inflation, velocity is enough of a non-problem that money is a reasonable proxy for wealth. To have a lot of money and to be wealthy are the same thing.

In stages two and three, having more money is a sure ticket to having less wealth.

The government’s greed has led it to create carloads of dollars out of thin air. Its main purpose has been not to hoard the dollars, but to trade them for real wealth, for valuable goods and services. The wise investor will do the same. Be a seeker of wealth, not money.

This is a big part of the reason EWR’s investment tactics have been so successful. If you are a long-time reader, you recognize that ever since the beginning of the war, I have been steering you away from dollars and toward wealth.

I doubt either the war or its inflation will go away in my lifetime (I’m a healthy 61), so the best advice I can give you is, become an expert about inflation, money demand and velocity.

To a large extent, you already are, if you’ve read the four short economics books in my Uncle Eric series, and I expect you are much wealthier because of it. Congratulations!

Sometimes even people who are geniuses in their own complex fields have a difficult time with economics and finance, where they don’t have much experience. The Uncle Eric books are written for those who want explanations that are fast and simple — that don’t require a lot of time or deep concentration.

1 OPEC is a permanent intergovernmental organization of 12 oil-exporting developing nations that coordinates and unifies the petroleum policies of its member countries. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/17.htm

2 “Saudi minister warns…” London Telegraph web site, 18 Nov 07.

3 “The Dollar: Shrinkable…,” N.Y. Times web site, 11 May 08.

4 Ibid. “The Dollar…,” N.Y. Times web site, 11 May 08..

5 “Libya Sours on U.S…., Wall St. Jrl., 16 May 08, p.1.

6 “Economics focus,” The Economist, 10 May 08, p.88.

7 Fiat Money Inflation in France, by Andrew Dickson White, Caxton Printers, USA, 1958, p.62.

8 The Great Inflation by Guttmann and Meehan, Clifford Frost Ltd., 1976, chapter 2.

9 Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls, by Schuettinger and Butler, Heritage Foundation, 1979, p.42.

10 Ibid. Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls, p.50.

11 Ibid. The Great Inflation, p.151.

12 See Harry’s short book Fail-Safe Investing, www.harrybrowne.org

Copyright ©2025 Henry Madison Research, Inc. | P.O. Box 84908, Phoenix, AZ 85071 | 800-509-5400 | A Proud U.S. Company